Other than on Eurozone matters, of which more below, there is also no institutional separation, no two-tier structures or separate institutions apart from, in the Council, differentiated voting, but with everyone around table. In the Commission, Parliament and Court, there is no differentiated voting.

The sole exception to this is on Eurozone matters, where there are separate (under the treaty, "informal") meetings of the Eurogroup of finance ministers and Eurozone Summits at the level of heads of state or government (but even those have the same President as the European Council, and its meetings are normally held in conjunction with European Council meetings). And on Eurozone matters too, Commission, Parliament and Court remain whole, with no differentiated voting. But what about further deepening of the Eurozone? Clearly those sharing a common currency are having to do more together to manage their common currency. Does this potentially lead to two-tier Europe? It evidently does to a degree, and this has already happened in large part. But I see seven reasons why it will not lead to fully fledged two-speed Europe.

-

First, the group is clearly not an avant garde on any other subject than those directly linked to the common currency (not foreign policy, justice, environment, transport, agriculture, fishing, consumer protection, competition policy, etc.)

-

Second it is not a fixed membership group, others will join, only two have legal opt-outs (and even they have a right to reconsider). It is not a fixed-boundary division.

-

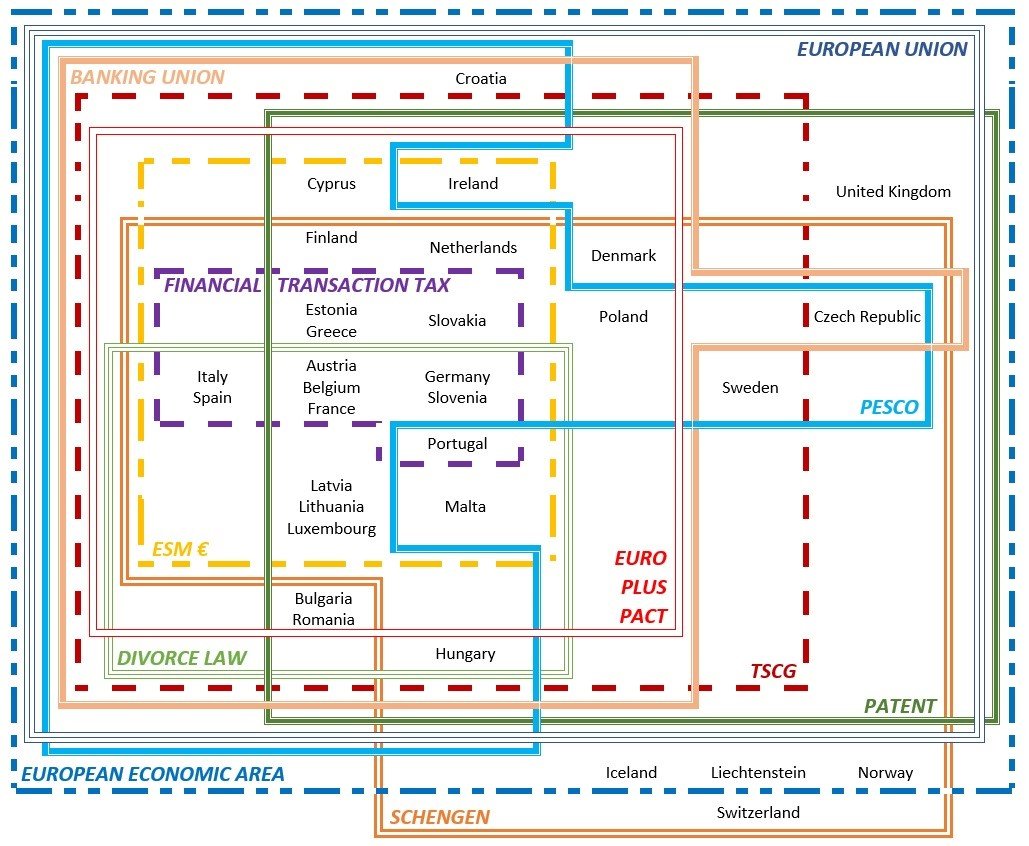

Third, the deepening measures which have been taken as response to economic crisis, have, in many cases, been at the level of the whole Union, and only some at level of the euro. For example, the three European Supervisory authorities for the financial sector (European Banking Authority, etc), the European Systemic Risk Board, substantial legislation on the financial sector, the reinforced excessive deficit procedure, the EU Semester as a means of intensifying macroeconomic policy co-ordination, have all been done at the level of the whole Union.

-

Fourth, what HAS been done at eurozone level, has usually been done in a way that was deliberately open to others to participate, and attempts have been made to expressly minimize the institutional split between the 17 and the rest. For example: the Stability Treaty ("Fiscal compact"), was done at level of eurozone, but almost all the others wanted to join and in the end only two did not sign it. Furthermore its architecture was designed to keep it as close as possible to the EU system. Another example, currently underway, the banking union: although one could argue that this is needed for the single financial market as much as for the single currency, it was done at level of eurozone + others that wanted to join -- but every care was made to ensure single market compatibility, including a "double majority" voting procedure to safeguard the "outs". Further example: the Eurozone Summits: these are being held in conjunction with European Council meetings, not stand-alone. Everyone can raise an issue before the 17 meet separately. It has been given the same President to ensure institutional coherence. Also, at least one of the two annual meetings is open to all signatories of the Stability treaty, not just the Eurozone.

-

Fifth , the bulk of what the EU does, even economically, is at the level of the whole EU of 28. The single market is crucial in this respect, it is the glue that holds EU together and generates bulk of EU legislation. The common rules on consumer protection, competition, state aids, standards, etc, etc, is at level of whole EU. So is trade policy, environment, R&D programmes, and of course all the non-economic matters such as foreign policy, police & justice, etc.

-

Sixth, no separate institutional structures have been set up, other than the ESM. The ESM is indeed intergovernmental at eurozone MS level. After all, it is financed by national money or guarantees (the EU budget is far too small) and the Member States are the shareholders, so they sit on the board of governors. In practice, however, when it comes to using this instrument, they rely on the Commission for country specific reports, to negotiate MoUs, etc.

-

Last, in the case of the Stability Treaty, its architecture has been designed to avoid divergence. (It was not even originally intended to have a separate treaty -- that resulted from UK non-cooperation in December 2011.) Every care has been taken to hug the EU institutions closely: role of Commission, use of ECJ, etc. And not just Eurozone Member States, but all bar two Union Member States joined in, so rather than being a separate construction, the correct analogy is that of my colleague Luuk Van Middelaar, that it is a buttress, supporting the main structure, not a separate building.

There are, of course, different narratives about all of this, not just in academia, but also among Member States. Nonetheless, the compromises reached do limit the two-tier divergence.

So far, so good. But what of the future? Is there possible treaty change coming? In general we find that much can be done within existing treaties, more than perhaps initially considered possible. And many of the things for which treaty change would be necessary are things for which there is anyway no consensus (like fully fledged Eurobonds). The procedure for treaty change is long and difficult. And now, the situation in the UK doesn't encourage others to go down the route of treaty change. What, indeed, about Cameron's January 2013 speech? That speech was more as party leader, rather than as government leader, and about what a future UK government would do, if the Conservatives win absolute majority in 2015. Up to now no other major party has matched that pledge. There is therefore no certainty yet that further opt-outs or renegotiation or devolution will be on the table in the way that Cameron seemed to envisage. If this eventuality does arise, it remains to be seen what emphasis will be given to multilateral reforms or to unilateral opt-outs, what other Member Sates are willing to accept, and whether the focus will be primarily on treaty change or changes to legislation.

To conclude, expectations of an emerging two-tier system must be nuanced by a host of factors that limit the division into two tiers, blur the boundaries and maintain the primary importance of the whole Union.

(*)

opt-in..: to decide that you want to do something or be involved in something;

opt-out: to decide not to take part in something or to stop taking part in it. |