| ON STAGNATION

Europe must not cut, but spend money'. The financial crisis was caused by too much confidence, too much money lending and to much spending, but the irony is that the crisis can only be solved by more confidence, even more more money to lend and spend, says Larry Summers, the former US Minister of Finance October 29, 2014 during the annual Tinbergenlecture at the Dutch National Bank.

The former Harvard president and economic advisor to President Obama is known as a gifted economist. Summers was named last year as the new chairman of the Federal Reserve, the US central banking system. He is known for his direct and sometimes blunt manner. Summers brought his message outspoken. The US economy is performing 'properly', but not great, he said. Certainly not given the massive stimulus the central bank has taken since the outbreak of the crisis. The eurozone economy is doing even "lousy" and remains far behind the expectations. Europe has not yet noticed that it is on the Japanese road.

There is the situation of prolonged underperformance, where interest rates of around 0 percent and deflation seems inevitable. Japan is trying to turn the tide by creating large amounts of money, but so far only partly succeeds. Recently the central bank announced to pump tens of billions a year extra into the economy. In the eurozone too, the inflation is coming closer to zero.There is talk of "secular stagnation" says Summers: 'sickly recovery that dies in infancy', he quoted Alvin Hansen, the Keynesian economist who described the mechanism in 1938. According to Hansen, the only way is that governments start issuing a lot of money in order to stimulate investment and spending.

Of course it feels counter-intuitive, he said, to provide just more money in tough times. When I ask an American audience who is proud of Kennedy airport no one raises his hand. I say: now you can fixing up 'with money you borrow at negative rates. When will there be again an opportunity pass?'

But instead to invest in infrastructure, governments choose for cutting and advancing investment. Policies that they can not justify to the younger generations, Summers said. They will then have a carry a much heavier bvurden than an interest rate of zero percent, he predicts. 'The three percent norm by the European Union for the budgets of the Member States is therefore absurd. France had just at this point quite right, when earlier this month a too broad a budget proposal was submitted to Brussels and was rebuffed. Demanding structural reforms from France, the European Union and Germany ahead, are not the solution for secular stagnation'.

'It has just as good as nothing to do with it', says Summers. Moreover, it is attempted in the eurozone for years. Also, monetary policy can not offer a real solution, the economist thinks. It is questionable whether a major expansion program, such as has just finished in America and Japan is performing now, is effective in the eurozone. I have no objection, but the knowledge we now have notes that more public investment would be better. Whether this is politically feasible in Brussels, depends on who it represents, says Summers. If it comes from an Italian career civil servant, it is taken a lot less serious than when it is suggested by someone from a country where the budget is generally in order.

ABOUT BUBBLES

|

| George Soros, Prof Robert J. Shiller, Jean-Paul Rodrigue, (dept. of Global Studies & Geography, Hofstra University) and Alan Greenspan claims that stages in bubble business cycles are a well understood concept. |

Soros lectured 17-04-2008 that markets are not out of trouble yet. What we see now is a period of instability (and uncertainty).

Maintaining stability has to be the objective of the authorities by a more semantic rule of regulations. Not only money supply but also credit supply and hedgefunds need to be controlled. He also stated there is a commodities bubble still in the growth phase.

Prof Shiller stated that the huge rise in house prices in the U.S. can not be explained by interest or demographics, but by presence of areal bubble which can be compared to epidemics and Jean-Paul Rodrigue claims claims that stages in a bubble business cycles are commonly linked with technological innovations, which are often triggering a phase of investment and new opportunities in terms of market and employment.

|

|

|

|

19-03-2010: SOUNDBITE (English) by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Managing Director of International Monetary Fund (IMF): regulation and supervision are OK. It is on track. Maybe discussion about technical points. I am confident that the target will be reached. But I do not sense the same momentum in the area of crisis management and resolution. The existing arrangements have proven to be inadequate. Taxpayers in many countries are paying the price for crisis management and resolution frameworks that insufficiently protected their interests. What is needed in our view is a European resolution authority with the mandate and the tools to deal with failing cross-border banks. It has to be part of an integrated system of crisis prevention and management. It should cover the major cross-border banking groups and other banks running large-scale cross-border operations under the single European passport |

Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency and worldwide payment system and the first decentralized digital currency, as the system works without a central bank or single administrator, may now be the biggest financial bubble of all time. bitcoin now looks to be bigger than any of the 10 other market bubbles it studied including the the tech bubble, beanie babies, the Dow in 1929 and the silver bubble of the late 1970s.

ON THE DEBT ISSUE

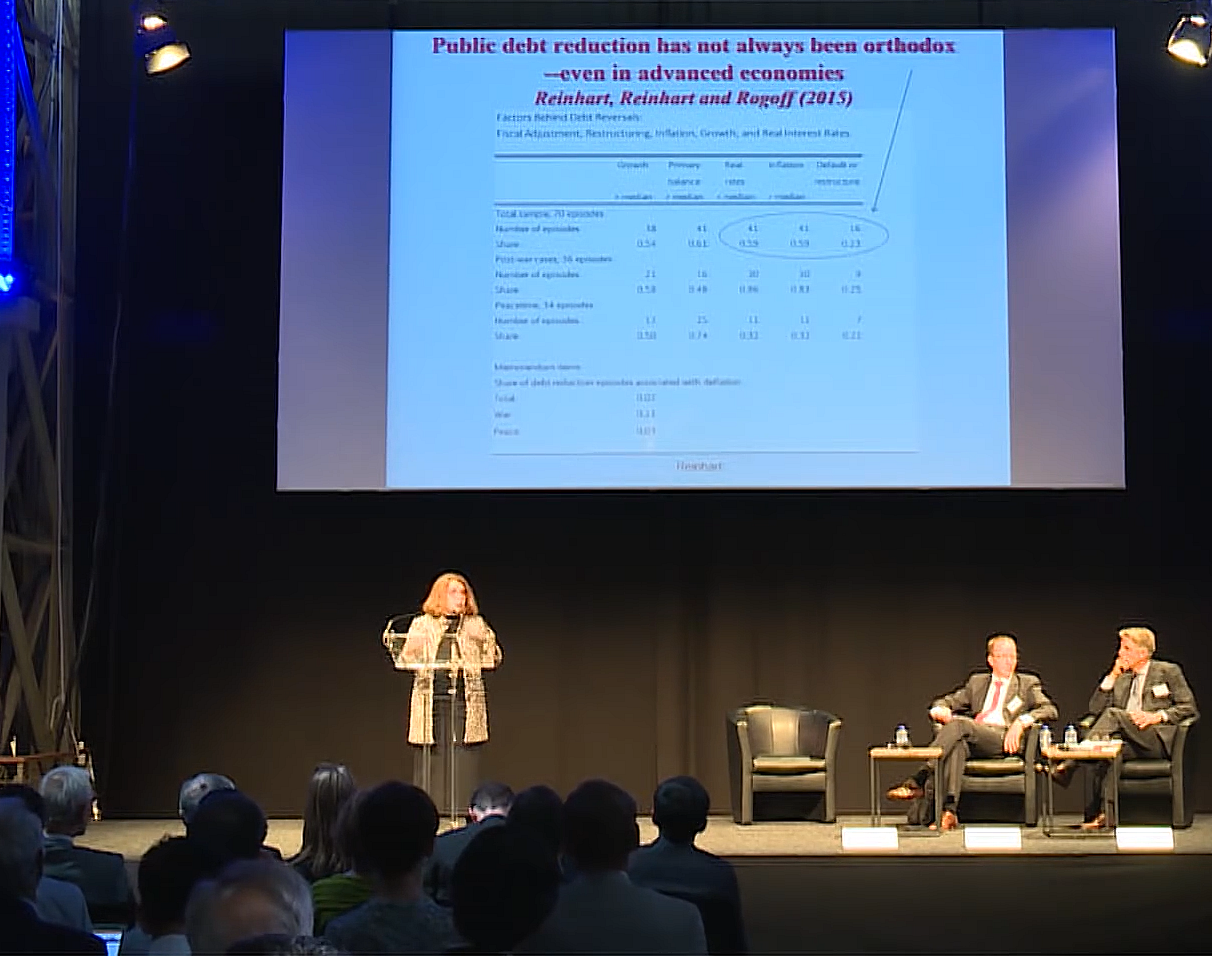

On the debt issue, Prof.dr. Carmen Reinhart (Harvard University, University of Maryland and PIIE), e.g. co-author of 'This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly' (with Kenneth Rogoff) delivered Friday 19 October 2012 the lecture 'A Decade of Debt' by which she addressed the variations on debt themes such as debt overhang, deleveraging, unemployment and double dips in most advanced economies, the European risks from financial crash to debt crisis and more restructurings, the 'capital inflow problem' of the major emerging markets and a global issue of the return of financial repression. The developed countries must find a

way to navigate between the Scylla of insufficient stimulus for their weak

economies and the Charybdis of excessive issuance of public debt, which

would endanger its risk-free status and thus deprive their economies of an

indispensable benchmark. To ward off the threat of a worldwide depression that loomed at the end of the 2000s, governments opted to run up substantial fiscal deficits. In doing so, they sowed the seeds of the sovereign debt crisis.Saddled with often high debt burdens and modest growth prospects, developed countries’ governments must now rebalance their budgets. Doing so too rapidly, however, will choke growth. The developed countries must find a

way to navigate between the Scylla of insufficient stimulus for their weak

economies and the Charybdis of excessive issuance of public debt, which

would endanger its risk-free status and thus deprive their economies of an

indispensable benchmark. To ward off the threat of a worldwide depression that loomed at the end of the 2000s, governments opted to run up substantial fiscal deficits. In doing so, they sowed the seeds of the sovereign debt crisis.Saddled with often high debt burdens and modest growth prospects, developed countries’ governments must now rebalance their budgets. Doing so too rapidly, however, will choke growth.

Faced the debt dilemma, Japan and the United States have pursued growth policies while the euro area members are quickly trying to rebalance their budgets. There are respective risks associated with these two strategies and for the international monetary and financial system of developing countries.

|

|

On 1 July 2011 CEPS delivered the commentary 'History repeating itself: from the Argentine default to the Greek tragedy?' Since the onset of the debt crisis in late 2009, the comparisons between Greece and

Argentina have multiplied, with an emphasis more on the similarities than the

differences. This is not surprising given the stunning parallels.

The commentary

draws a systematic comparison between the two countries over the decade before the crisis

and the management of the crisis.

Overall it suggests that there may be little left to do for

Greece to avoid a repeat of the Argentine default, but in larger scale.Debt reduction without default? This paper by Daniel Gros and Thomas Mayer proposes a two-step, market-based approach to debt reduction: offer holders of debt of the countries with an EFSF

programme an exchange into EFSF paper at the market price prior to their

entry into an EFSF-funded programme and once the EFSF had acquired most of the debt, it would assess debt sustainability country by country. Key characteristic of a boom is the expansion of leverage (i.e.

private debt). The key characteristic of the subsequent bust is the explosion of public debt as

private debt cannot be serviced. The economies of Ireland and Latvia (and to some extent Spain)

offer good examples of this trend of adjustment difficulties in the piigs club.

Within the euro area, however, it is no longer possible to make such a clear distinction between

public and private debt given that no euro area country has access to the printing press. Imbalances within the euro area have been a defining feature of the crisis. The paper 'Adjustment in Euro Area Deficit Countries' provides a critical analysis of the ongoing rebalancing of euro area “deficit economies” (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain) that accumulated large current account deficits and external liability positions in the run-up to the crisis. It shows that relative price adjustments have been proceeding gradually. Real effective exchange rates have depreciated by 10-25 percent, driven largely by reductions in unit labor costs due to labor shedding. While exports have typically rebounded, subdued demand accounts for much of the reduction in current account deficits. Hence, the current account balance of the euro area as a whole has shifted into surplus.

Internal rebalancing has come with subdued activity—notably very high unemployment in the deficit economies—and made continued adjustment more difficult. To advance rebalancing further, the paper emphasizes the need for:

- macroeconomic policies that support demand and bring inflation in line with the ECB’s medium-term price stability objective;continued EMU reforms (banking union) to ensure proper financial intermediation; and

- structural reforms in product and labor markets to improve productivity and support the reallocation of resources to tradable sectors.

Already much is written about macroeconomic imbalances in the euro area and symmetry in the eurozone. Lax financial conditions can foster credit booms, that led to large capital flows across the world, including large movements of resources from the Northern countries of the euro area towards the Southern part. After 2009, these flows have suddenly stopped, creating severe adjustment pressures. The challenge is to strike a delicate balance between providing liquidity for solvent institutions while keeping the overall pressure on for a rapid correction of the imbalances.The divergence of the competitive

positions that have built up since the early 2000s is one of the major problems of the eurozone. This divergence has led to major

imbalances in the eurozone where the countries that have seen their competitive

positions deteriorate (mainly the ‘PIIGS’ – Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) have

accumulated large current account deficits and thus external indebtedness, matched by

current account surpluses of the countries that have improved their competitive positions

(mainly Germany).

ON GROWTH

Both President Barroso and M. El-Erian addressed the dilemma of expansion versus austerity. Barrosso during the Brussels Think Tank Dialogue 2013 and

M. El-Erian in June 2010: In one corner stand the “growth now” camp, arguing that expansion is a pre-requisite to service their debt sustainably.

Without it tax receipts implode, investment is turned away, and meeting future debt payments is harder. Against them stand the “austerity now” camp. By the Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2013 the to austerity related interesting article ‘EU fires back in Austerity Debate’ from Matthew Dalton was posted: The economists of the European Commission are under fire. Critics are blaming them for pushing austerity policies that are partly responsible for Europe’s dreadful economic situation. Worst of all, Paul Krugman is comparing their ideas to disgusting insects.

On Wednesday, commission economists fired back at their critics in nearly 3,000 eye-glazing words of economics jargon. Here are their basic points, in relatively plain English: The commission responds to an argument by the economists Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji that Europe’s austerity policies were an overreaction to the market panic that hit Greece, then Ireland and Portugal starting in 2010. Supporting De Grauwe and Ji is the fact that the relative market calm the euro zone now enjoys arrived only after the European Central Bank announced it would buy unlimited quantities of bonds of countries that sign up for a bailout program. If only the ECB had made that pledge at the beginning of the debt crisis, maybe drastic austerity wouldn’t have been necessary, or so the argument goes. |

|

Not so, the commission says. Falling government borrowing costs in the euro-zone periphery aren’t just the ECB’s doing: “The growing perception that adjustments are underway likely also contributed to the improvement in markets,” according to the paper, which was written by Marco Buti, the top civil servant in the commission’s economics division, and Nicolas Carnot, an adviser at the division.

Budget deficits in the periphery are falling; so are current-account deficits, suggesting an improvement in the underlying competitiveness of these countries. But the paper doesn’t really elaborate on that argument. The burden of proof seems to lie with the commission on this one, since the effect of the ECB pledge was so dramatic. Was budget austerity – or rather “fiscal consolidation” – necessary at all in Europe? The commission believes yes, and it notes the International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development believe so too. Therefore budget austerity is, in fact, necessary?

“Once it is admitted that fiscal adjustment is due, the issue becomes not one of principle but of degree,” according to the paper. But what if it is not admitted? What if instead it is argued that the euro zone as a whole shouldn’t have reduced its deficit? Clearly Greece, Portugal and Ireland, facing severe market pressure, needed to cut. But did Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Austria or even France? All of these countries faced low funding costs throughout the crisis and no immediate need for austerity.

Having Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and Austria – the euro zone “core” – run bigger deficits would have softened the euro zone’s budget stance; stimulus in the core would at least have prevented the euro-zone budget deficit from falling as fast as it did, or falling at all. Doing so would also have increased long-dormant domestic demand in the euro-zone core and helped the periphery recover through export-led growth. The commission is on board with this point. “We would agree that the symmetry of the adjustment is a legitimate concern,” they write, “There are ways to favour a coordinated approach to rebalancing, but the currently available tools also present limitations.” The commission notes that Germany is edging towards better policies. The government’s budget stance is now basically neutral – neither cutting nor stimulating. German officials have said they are willing to allow stronger wage increases, which will help German consumers buy goods made by Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Irish factories. The problem is, this is arguably too little, too late. Germany has been cutting its deficit for the last two years. German wage inflation or overall inflation hasn’t been much higher than in the periphery. And that continues to be the case. Without higher inflation and stronger domestic demand in the euro-zone core, the periphery is facing a long, nasty period of adjustment. The commission also defends itself against the charge of being inflexible. Over the last year, it has given more time to Spain, Portugal and Greece to cut their budget deficits, because weak growth has undermined deficit targets. “Further extensions of deadline may be recommended in the near future,” Messrs. Buti and Carnot write.

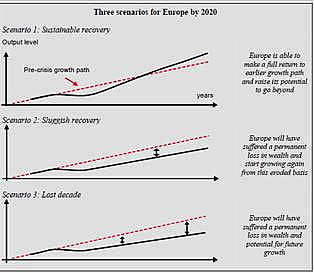

“The simple allegation that the Commission pursues austerity inflexibly does not hold.” Over the last two years, we have faced the world's worst economic crisis since the 1930s. This crisis has reversed much of the progress achieved in Europe since 2000. We are now facing high levels of unemployment, sluggish structural growth and excessive levels of debt. The economic situation is improving, but the recovery is still fragile. At the same time, the world is moving fast and long-term challenges – globalisation, pressure on resources, climate change, ageing – are intensifying.

Europe can succeed if it acts collectively, as a Union. The Europe 2020 strategy put forward by the Commission sets out a vision of Europe's social market economy for the 21st century. It shows how the EU can come out stronger from the crisis and how it can be turned into a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy delivering high levels of employment, productivity and social cohesion. To deliver rapid and lasting results, stronger economic governance will be required.Following the Commission's communication "Europe 2020" and the discussions held in the Council, on the 25-26 March 2010, the European Council reached an agreement on the new strategy, which was formally adopted on 17 June. Europe has identified new engines to boost growth and jobs. These areas are addressed by flagship initiatives:

Within each initiative, both the EU and national authorities have to coordinate their efforts so they are mutually reinforcing. The recent financial crisis came about because a bubble burst. Keeping this in mind leads us to important

considerations Daniel Gros wrote January 2010 in a paper 'The impact of the crisis on the real economy'. November 2008 the Commission framed A European economic recovery plan, that has two key pillars, and one underlying principle. |

|