Christianity regards the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts, the Old Testament and the New Testament, as authoritative: written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and therefore the inerrant Word of God. Protestants believe that the scriptures contain all revealed truth necessary for salvation (See Sola scriptura).

The Old Testament contains the entire Jewish Tanakh, though in the Christian canon the books are ordered differently and some books of the Tanakh are divided into several books by the Christian canon. The Catholic and Orthodox canons include the Hebrew Jewish canon and other books (from the Septuagint Greek Jewish canon) which Catholics call Deuterocanonical, while Protestants consider them Apocrypha.

The first four books of the New Testament are the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), which recount the life and teachings of Jesus. The first three are often called synoptic because of the amount of material they share. The rest of the New Testament consists of a sequel to Luke's Gospel, the Acts of the Apostles, which describes the very early history of the Church, a collection of letters from early Christian leaders to congregations or individuals, the Pauline and General epistles, and the apocalyptic Book of Revelation

Some traditions maintain other canons. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church maintains two canons, the Narrow Canon, itself larger than any Biblical canon outside Ethiopia, and the Broad Canon, which has even more books. The Latter-day Saints, though generally not considered Christian, hold the Bible and three additional books to be the inspired word of God: the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price.

Interpretation

Though Christians largely agree on the content of the Bible, no consensus exists on its interpretation, or exegesis. In antiquity, two schools of exegesis developed in Alexandria and Antioch. Alexandrine interpretation, exemplified by Origen, tended to read Scripture allegorically, while Antiochene interpretation adhered to the literal sense, holding that other meanings (called theoria) could only be accepted if based on the literal meaning.

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into the allegorical, moral, and anagogical senses. The literal sense is "the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation." The allegorical sense includes typology, for example the parting of the Red Sea is seen as a "type" of or sign of baptism; the moral sense contains ethical teaching; the anagogical sense includes eschatology and applies to eternity and the consummation of the world. Catholic theology also adds other rules of interpretation, which include the injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal, that the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held, that scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church", and that "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome."

Many Protestants stress the literal sense or historical-grammatical method, even to the extent of rejecting other senses altogether. Martin Luther advocated "one definite and simple understanding of Scripture". Other Protestant interpreters make use of typology. Protestants characteristically believe that ordinary believers may reach an adequate understanding of Scripture because Scripture itself is clear (or "perspicuous"), because of the help of the Holy Spirit, or both. Martin Luther believed that without God's help Scripture would be "enveloped in darkness", but John Calvin wrote, "all who refuse not to follow the Holy Spirit as their guide, find in the Scripture a clear light." The Second Helvetic Confession said, "we hold that interpretation of the Scripture to be orthodox and genuine which is gleaned from the Scriptures themselves (from the nature of the language in which they were written, likewise according to the circumstances in which they were set down, and expounded in the light of like and unlike passages and of many and clearer passages)." The writings of the Church Fathers, and decisions of Ecumenical Councils, though "not despise[d]", were not authoritative and could be rejected.

Creeds

Creeds, or concise doctrinal statements, began as baptismal formulas and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the fourth and fifth centuries. The earliest creeds still in common use are the Apostles' Creed (text in Latin and Greek, with English translations) and Paul's creed of 1 Cor 15:1-9.

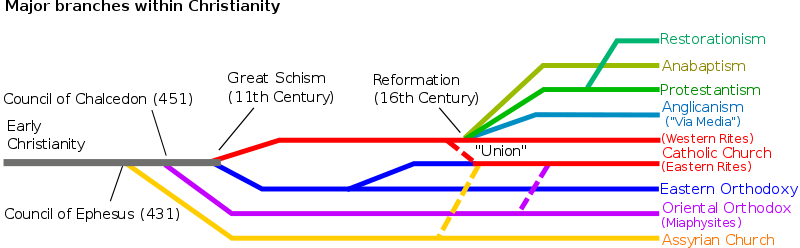

The Nicene Creed (Greek liturgical text, Latin liturgical text, English translations), largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively, and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the Council of Ephesus in 431.

The International Consultation on English Texts translation has been widely adopted by English-speaking Christians.

The phrases "God from God" and "and the Son" (the latter a matter of theological controversy and presented in brackets in the ICET translation) were not included in the text adopted by the First Council of Constantinople and confirmed by the Council of Ephesus, and as such are not used by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Chalcedonian Creed, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, (though not accepted by the Oriental Orthodox Churches) taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, that both natures are perfect but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person.

The Athanasian Creed (English translations), received in the western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons not dividing the Substance."

Most Protestants accept the Creeds. Some Protestant traditions believe Trinitarian doctrine without making use of the Creeds themselves, while other Protestants, like the Restoration Movement, stand against the use of creeds.

Eschaton and afterlife

Most Christians believe that upon the death of the body, the individual soul, which is considered to be immortal, experiences the particular judgment and is either rewarded with heaven or condemned to hell. The elect are called "saints" (Latin sanctus: "holy") and the process of being made holy is called sanctification. In Catholicism, those who die in a state of grace but with either unforgiven venial sins or incomplete penance undergo purification in purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into heaven.

At the last coming of Christ, the eschaton or end of time, all who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgement, whereupon Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.

Some groups do not distinguish a particular judgment from the general judgment at the end of time, teaching instead that souls remain in stasis until this time (see Soul sleep). These groups, and others that do not believe in the intercession of saints, generally do not employ the word "saint" to describe those in heaven. Universalists hold that eventually all will experience salvation, thereby rejecting the concept of an eternal hell for those who are not saved.

|