|

|

|

|

| Free Trade, Economic Security, Tariffs |

| Tariffs and what may lie ahead for the global economy

Has history given us any case where tariffs did more good than harm?

Adam Smith, as a matter of principle, thought no, never.

Donald Trump disagrees. Or does he? Will he stop short of a tariff war if he gets something he wants?

Is he just a dealmaker from Queens, New York, huffing and puffing and bluffing, ready to accept a deal after strutting and showing off to his fans? |

|

|

On (history of) TRADE, TARIFFS and the (Global) Economy |

| Europe balancing between Trade Wars and Economic Security

Against a backdrop of new tariffs, trade wars and an unpredictable trade policy under te new Trump presidency, the European Union and its Member States have to navigate an increasingly challenging geo-economic landscape. While free trade was the credo during much of past century, multilateralism is under pressure. The World Trade Organization, whose dispute settlement system is currently dysfunctional, is no longer an effective form to resolve trade disputes between countries. But trade wars are only one piece in a complex puzzle and the EU has to constantly balance between free trade, competitiveness and economic security: as the Drahgi Report pointed out in 2024., the EU must double down on supporting its strategic sectors such as critical technology, raw material, defence and energy, while taking into account its economic security in a more geopolitical and multipolar world of vulnerable supply chains. For this reason, the EU has also developed a new European Economic Security Strategy. The Strategy proposes to carry out a thorough assessment of risks to economic security in four areas:

|

| TRUTHS ABOUT TRADE |

| (speech by Cecilia Malmström, European Commissioner for Trade, talks on the truths of EU trade at the Bruegel Annual Meetings 2019)

Today I want to discuss truth. In the age we live in – of instant communication, simplified messages and government by Twitter – truth can be difficult to hold on to. There is a quote, attributed to Mark Twain: “A lie travels around the globe while the truth is putting on its shoes.” It is a famous quote, and very apt – especially given that there is no evidence that he said it. Today, many in this room will agree on most things – but we will disagree on others. And in my experience, it is always good to find a mutual point to start on. So, let me suggest one: Ladies and Gentlemen – the earth is round. Or to be accurate: an oblate spheroid. Life would be easier if it were flat:

But unfortunately it is not flat – a fact first proved in the 3rd century BCE, when Hellenistic astronomy calculated its shape and circumference. Since then, the evidence has mounted up. From astronomical calculations to simple observation. From ground-level views to photos from aircraft and spacecraft. |

|

|

Often you hear people say that they are entitled to their opinion – That’s of course true, but even so, your beliefs should guide you, but not all decisions can be gut decisions. If you want to disagree with something, you have a responsibility to look at and understand the evidence. This is something that has become very clear to me in my time as Commissioner for Trade. I am a proud liberal – I believe in open borders and free trade. My ideological beliefs have guided me – but sometimes I must recognise the reality of a situation that is constantly evolving, even where I have had some initial doubts. So today I want to talk to you about a few things in trade – specifically: the things that feel intuitively true, but are in fact not, and what lessons we can draw from this for the future. |

|

|

|

|

| HOW FAR SHOULD WE PUSH GLOBALIZATION? |

| 4 November 2016, Paul de Grauwe

The discussions about CETA, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union, have focused almost exclusively on two questions. They are important but certainly not the most fundamental ones. In this article I first discuss these two questions and then turn to the more fundamental question of how far we should push globalisation. The first question at the centre of the debate around CETA concerns the way national regulations on environment, safety and health are made consistent with each other. To make trade possible in a world where trading partners have different rules about the environment, health and safety, a procedure must be followed to make these rules mutually acceptable. When, for example, two countries wish to trade in poultry, they must agree on what constitutes a healthy chicken. The attitude of many opponents of CETA in Europe is that European regulation is superior to the Canadian (or American in the context of TTIP), and that as a result Canadian and American chicken are suspect, if not poisonous. The implicit hypothesis of this attitude is that European governments care more about the health and safety of their citizens than the Canadian and American governments do about their citizens. |

Such an attitude makes trade agreements very difficult. Moreover, it is not based on facts. There is no reason to assume that European legislation of health, safety and the environment is superior to the North American one. If that were the case, the European regulators would long ago have curbed the harmful emissions of rigged European-made diesel cars. They did not, the US authorities did.

The second question at the forefront of the CETA negotiations had to do with the legal procedures to resolve disputes between foreign investors and national authorities. The CETA trade agreement, like many others, provides that foreign investors who feel harmed by new environmental, health, and safety regulations can turn to a special arbitration procedure. This is indeed a problem. It would be better to accept the jurisdiction of national courts in these matters, rather than to allow international investors to turn to special arbitration courts. The feeling in many countries that this is unacceptable discrimination mostly favouring multinational corporations should be respected. While it is preferable to rely on national courts to settle disputes, I have the impression that the opponents of CETA (and TTIP) have blown this problem out of proportion, even arguing that the ratification of these trade agreements would undermine the foundations of our democracy. A more fundamental question that has not been sufficiently addressed in the discussions around CETA is: How far we should push globalisation? In my academic career I have always been an advocate of free trade. Free trade provided the basis of the phenomenal material prosperity we have achieved in Europe in the post-war period. It has also made it possible for hundreds of millions of people, especially in Asia, to be pulled out of extreme poverty and to live a decent life. |

|

But it now appears that globalisation is reaching its limits. These limits exist for two reasons. Firstly, there is the environmental limit. Globalisation leads to very strong forms of specialisation. There is of course nothing wrong with specialisation as it provides the conditions for creating more material welfare. But specialisation also means that goods are frequently transported around the globe. The lengthening of the value chains that has been made possible by the reduction of trade tariffs means that the same goods can travel back and forth between many countries before they reach the final consumer. All this transporting around the globe creates large environmental costs (e.g. CO2 emissions) that are not internalised in the price of the final product. As a result, the prices of these products are too low and too much of them is produced and consumed. Expressed differently, globalisation has made markets freer but these markets do not function properly, in that they give incentives to produce goods that harm the environment.

When the proponents of CETA (and TTIP) argue that trade agreements will lead to higher GDPs, they are right, but they forget to say that this will be accompanied by rising environmental costs. If we subtract the latter from the former, it is not certain that this leaves something positive. The second downside to globalisation has to do with the highly unequal distribution of its costs and benefits. Free trade creates winners and losers. As argued earlier, there are many winners from globalisation in the world, the most important being the hundreds of millions who used to live in extreme poverty. There are also many winners in the industrialised countries, e.g. those who work for or are shareholders in exporting companies. But there are also many losers. The losers are the millions of workers, mostly in the industrialised countries, who have lost their jobs or have seen their wages decline. These are also the people that have to be convinced that free trade will ultimately be good for them and their children. Not an easy task. If, however, we fail to convince them, the social consensus that has existed in the industrialised world in favour of free trade and globalisation will deteriorate further. The most effective way to convince the losers in the industrialised world that globalisation is good for them is to reinforce redistributive policies, i.e. policies that transfer income and wealth from the winners to the losers. But this is more easily said than done. The winners have many ways to influence the political process aiming at preventing this from happening. In fact, since the start of the 1980s when globalisation became intense, most industrialised countries have weakened redistributive policies. They have done this in two ways. First, they have lowered the top tax rates used in personal income tax systems. Second, they have weakened the social security systems by lowering unemployment payments, reducing job security and lowering minimum wages. All this was done in the name of structural reforms and was heavily promoted by the European authorities. Thus, while globalisation went full speed ahead, industrialised countries reduced the redistributive and protective mechanisms that were set up in the past to help those who were hit by negative market forces. It is no surprise that these reactionary policies created many enemies of globalisation, who are now turning against the policy elites that set these policies in motion. Let us now return to the question I formulated earlier: How far should we push globalisation? My answer is that as long as we do not keep in check the environmental costs generated by free trade agreements and as long as we do not compensate the losers of globalisation – or worse, continue to punish them for being losers – a moratorium on new free trade agreements should be announced. This is not an argument for a return to protectionism. It is an argument to stop the process of further trade liberalisation until we come to grips with the environmental costs and the harmful redistributive effects of free trade. This implies introducing more effective controls on CO2 emissions, raising the income tax rates of the top income levels and strengthening social security systems in the industrialised countries. |

| TTIP |

Launched back in 2013, the negotiations to complete a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are still very much ongoing, with political leaders presenting the trade deal as a huge opportunity for jobs and growth on both sides of the Atlantic. In the 2014 geopolitical climate and in the face of increasing international competition, leaders hope to use the deal to strengthen the ties between the EU and US, to reinforce the position of the two blocs as commercial and economic world leaders.

The original deadline for completion, the end of 2014, will soon have passed. With a new European Commission and Parliament, and following November’s mid-term elections to Capitol Hill, pressure is on negotiators to finalise the agreement by the end of 2015, and before President Obama’s mandate comes to an end. This pressure comes against a backdrop of increasing media hostility and public protest in Europe, and a scaling up of outreach efforts by proponents of the deal.

February 2013, Obama, Van Rompuy, Barroso gave the go-ahead for a transatlantic free trade deal, an economic 'grand projet' that could inject around 1% of fuel per year into the tank of economic growth by 2027: 0.5% in the EU, perhaps 0.4% in the US or a combined €150bn. Trade and, specifically, bi-lateral deals are now hailed as the new engines of growth. In the years to come, we need to seize the opportunity of higher levels of growth abroad, especially in East and South Asia. the EU has an elemental interest in securing a full-scale deal with the US. The agreement would wipe out the average 4% tariff and harmonise standards. But the bigger picture is that this would be a geostrategic game-changer. Transatlantic rules would be agreed between the US and Europe and those rules would set the standards that China and others would have to follow. This is not a pipe dream given that the US-EU economic relationship is already the world's largest, accounting for one third of total trade in goods and services and nearly half of global economic output. The deal would develop: "...rules and principles on issues of global concern, including on market-based disciplines for State-Owned Enterprises (that's you China), combating discriminatory localisation barriers to trade, and promoting the global competitiveness of small- and medium-sized enterprises. These negotiations will set a standard, not only for our future bilateral trade and investment, including regulatory issues, but also for the development of global trade rules." The WTO is less certain. April 2013, the European Parliament’s International Trade Committee (INTA) met and discussed the EU-US Trade Agreement and urge Council to launch trade and investment talks with US. The EU Council of Ministers should authorize the start of Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) talks with the US in June, say International Trade Committee MEPs in a resolution voted on Thursday. The negotiating mandate should include public procurement, the digital and ICT space, chemicals, automotive and transport, pharmaceuticals and health, energy and raw materials, agriculture, food and financial services, but exclude culture, they add. The Parliamentary committee’s role is to draft a resolution to empower the EU to enter negotiations with the United States. The resolution adopted by the Committee will be sent to the EU Parliament for approval. Parliament’s approval of the resolution will then empower the EU Council with the mandate it requires to officially negotiate on behalf of the EU with the United States. Once such a mandate is given, the EU Parliament must then approve the final agreement, although they cannot amend the agreement. The INTA Committee will consider a wide array of amendments for potential inclusion in the draft resolution on EU Trade and Investment negotiations (from which is suggested that the over-ambitious plans for investment protection should be dropped from the proposal) with the United States of America, including: - the 15 November 2012 digital freedom strategy, |

The focus of the draft resolution will largely be on regulatory barriers (technical requirements, safety issues, ingredients, GMO's etc). EU Trade Ministers met informally on the 18th of April in Dublin (Ireland) to discuss the EU’s trade priorities with fresh discussions taking place on the proposed EU-US Trade Agreement. EU Commissioner for Trade Karel De Gucht and International Trade Advisor to the US President, Mike Froman attended the meeting marking the first time a representative from the US Administration has discussed EU-US trade relations directly with EU Trade Ministers.

Minister Bruton, the Irish Minister who chairs the EU Trade Council for the duration of Ireland’s Presidency, commented “I’m delighted to say real progress towards achieving an agreement among Ministers has been made... This agreement is a crucial part in the process of starting negotiations on a new EU-US Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement”. The EU Council set an ambitious target of June for the agreement on a mandate to begin direct negotiations with the United States. On the US side, President Barack Obama has now taken all the necessary preliminary procedural steps, having notified Congress and requested public stakeholders’ input. Expectations that negotiations will begin to coincide with a trip to the EU in June/ July by the American President are high. In March 2013, the EU Commission released an Impact Assessment Report on the Future of EU US Trade Relations. The report considered the many advantages to increased trade between the two trading blocs. The report established that the EU as the largest economy in the world, representing 25.1% of world GDP and 17.0% of world trade with the US in second position with 21.6% of world GDP and 13.4% of world trade. Conclusion of a deal between the two trading blocs is expected to net an increase of 28% (or €187Bn) in exports to the US each year as well as increasing global trade, producing an additional 6% growth in exports for the EU. The total benefit is anticipated to be worth approximately €220bn and provide much needed job creation for both sides. Prime Minister David Cameron cited the potential of the deal to create two million jobs across the EU at the Davos talks earlier this year. The agreement will focus on market access, regulatory issues and non-tariff barriers as well as rules, principals and more generally on global themes likely to have far reaching influence on the global trading system such as a closer alignment on intellectual property protection and enforcement mechanisms. |

| Difficult areas for negotiation

Agriculture: in this sector there three main issues: subsidies, product controls and tariffs. With regard to subsidies, each partner operates an elaborate system of agricultural subsidies with significant political implications domestically if they try to modify or remove them. Some of the most difficult trade disputes between the EU and the US have related to food products. The dispute over the use of synthetic hormones in US beef ran from 1989 to 2009 and that over genetically modified organisms (GMOs) from 2004-06 but both issues will be raised by the US side. In both cases the dispute partly resulted from the EU acting in response to consumer concerns rather than scientific advice and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) found against the EU. There are some Member States that wish to ban GMOs again (although very few GMOs are authorised in the EU, especially for planting) but the Council has not been able to reach agreement. Geographic indicators are an additional area of concern in agriculture. The use of terms such as “champagne”, which are restricted under EU rules, is contentious in the US where they do not necessarily recognise the validity of the claims of a product to only come from a specific geographical area. As regards tariffs, the US has some very high tariffs on EU dairy products (up to 139 per cent), meat (30 per cent) and drinks (22-23 per cent), which the EU is keen to see reduced or abolished. Some EU goods are banned from importation into the US completely, including apples and some cheeses. On the other side, the EU retains high tariffs on most livestock products. |

Culture: The EU has rules to protect the audio-visual sector from non-EU takeovers and to allow public subsidies; this exemption from usual EU rules is in particular valued by France where it as seen as a safeguard against the French film industry being taken over by Hollywood. The French Government has suggested that it would veto an agreement that did not exclude culture (see below for further details).

Civil aircraft: The granting of subsidies to manufacturers of large civil aircraft in the US and the EU was governed from 1992 to 2004 by a bilateral agreement which reflected the fact that Boeing (USA) and Airbus (EU) are the two largest manufacturers of civil aircraft in the world. The US decided to withdraw from this agreement in 2004 and refer the matter to the WTO which ruled that both parties had broken the rules on subsidies. Discussions continue as the EU adopted counter-measures against the US in 2012. Defence: defence equipment is a contentious area in international trade and particularly so for the USA and the EU because they are the world’s key centres of design and manufacture of such goods. The US Congress has in the past been inclined to favour a buy USA policy in this field and several EU Member States are keen to protect their national defence industrial sector from US competition. Services: negotiating better access for services (both ways) will be challenging, as barriers to services generally involve behind-the-border regulatory issues. In the EU, some of these concern regulation that has not yet been harmonised via the Single Market. In the US, they include regulation at both federal and sub-federal level, with all the complications of securing agreement from independent federal regulatory agencies, on the one hand, and individual US states, on the other. And services include some contentious sectoral issues, among them widening transatlantic differences in financial services regulation. Other obstacles: other areas of dispute include the financial transactions tax, with US objections to the extra-territoriality provisions in the current proposals, air services, coastal shipping, the EU’s data protection rules and inward investment being frustrated by national rules. There are some significant cultural differences between the EU and the USA, for example over labour and consumer rights, that provoke dispute. The question of metric labelling is also an issue; US Federal law currently prohibits metric only labelling and requires both metric and US customary weights (similar to but not the same as UK imperial measures). This led the EU in 2009 to adopt a measure allowing supplementary labelling with non-metric measures in order to help companies exporting to the US (and the UK too). Differences over environmental standards also form an obstacle to agreement. Current trends Doha rounds The Doha round of World Trade Organization negotiations aims to lower barriers to trade around the world, with a focus on making trade fairer for developing countries. Talks have been hung over a divide between the rich, developed countries, and the major developing countries (represented by the G20). Agricultural subsidies are the most significant issue upon which agreement has been hardest to negotiate. By contrast, there was much agreement on trade facilitation and capacity building. The Doha round began in Doha, Qatar, and negotiations have subsequently continued in: Cancún, Mexico; Geneva, Switzerland; and Paris, France and Hong Kong. China Beginning around 1978, the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) began an experiment in economic reform. Previously the Communist nation had employed the Soviet-style centrally planned economy, with limited results. They would now utilise a more market-oriented economy, particularly in the so-called Special Economic Zones located in the Guangdong, Fujian, and Hainan. This reform has been spectacularly successful. By 2004, the GDP of the nation has quadrupled since 1978 and foreign trade exceeded $1 trillion US.

|

|

| ORGANISATION of TRADE |

|

Patterns of organising and administering trade include state control - trade centrally controlled by government planning and laws regulating Trade and establishing a framework such as trade law, tariffs, support for intellectual property, opposition to dumping. Guild control - trade controlled by private business associations holding either de facto or government-granted power to exclude new entrants.

In contemporary times, the language has evolved to business and professional organisations, often controlled by academia. For example in many states, a person may not practice the professions of engineering, law, law enforcement, medicine, and teaching unless they have a college degree and, in some cases, a license. Free enterprise - trade without significant central controls; market participants engage in trade based on their own individual assessments of risk and reward, and may enter or exit a given market relatively unimpeded. Infrastructure in support of trade, such as banking, stock market, and technology in support of trade such as electronic commerce, vending machines. International organisations: - European Common Market |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Types of trade: commodities, staple, luxurie, international trade, arms trade, wholesaling, retailer, stock exchange, fair trade. - Support for trade: infrastructure, computers and Internet, e-commerce, search engine, critical infrastructure, accounting, banking, insurance, public services (police protection and postal services), public utilities (telephone, fax, telephone directory, translation), transport (highways, railroads, ship transport). |

| HISTORY of TRADE |

Trade originated with the start of communication in prehistoric times. Trading was the main facility of prehistoric people, who bartered goods and services from each other when there was no such thing as the modern day currency. Peter Watson dates the history of long-distance commerce from circa 150,000 years ago. Trade is believed to have taken place throughout much of recorded human history. There is evidence of the exchange of obsidian and flint during the stone age.

Materials used for creating jewelry were traded with Egypt since 3000 BC. Long-range trade routes first appeared in the 3rd millennium BC, when Sumerians in Mesopotamia traded with the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley. The Phoenicians were noted sea traders, travelling across the Mediterranean Sea, and as far north as Britain for sources of tin to manufacture bronze. For this purpose they established trade colonies the Greeks called emporia. Trading is important to the global economy. From the beginning of Greek civilization until the fall of the Roman empire in the 5th century, a financially lucrative trade brought valuable spice to Europe from the far east, including China. Roman commerce allowed their empire to flourish and endure. Their widespread empire produced a stable and secure transportation network that enabled the shipment of trade goods without fear of significant piracy. The fall of the Roman empire, and the succeeding Dark Ages brought instability to Western Europe and a near collapse of the trade network. Nevertheless some trade did occur. For instance, Radhanites were a medieval guild or group (the precise meaning of the word is lost to history) of Jewish merchants who traded between the Christians in Europe and the Muslims of the Near East. |

From the 8th to the 11th century, the Vikings and Varangians traded as they sailed from and to Scandinavia. Vikings sailed to Western Europe, while Varangians to Russia. Through the 11th and 12th centuries medieval world's trade networks arose, and the Hanseatic League was an alliance of trading cities that maintained a trade monopoly over most of Northern Europe and the Baltic, between the 13th and 17th centuries. Vasco da Gama restarted the European Spice trade in 1498. Prior to his sailing around Africa, the flow of spice into Europe was controlled by Islamic powers, especially Egypt. The spice trade was of major economic importance and helped spur the Age of Exploration. Spices brought to Europe from distant lands were some of the most valuable commodities for their weight, sometimes rivaling gold.

In the 16th century, Holland was the centre of free trade, imposing no exchange controls, and advocating the free movement of goods. Trade in the East Indies was dominated by Portugal in the 16th century, the Netherlands in the 17th century, and the British in the 18th century. In 1776, Adam Smith published the paper An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It criticised Mercantilism, and argued that economic specialisation could benefit nations just as much as firms. Since the division of labour was restricted by the size of the market, he said that countries having access to larger markets would be able to divide labour more efficiently and thereby become more productive. Smith said that he considered all rationalisations of import and export controls "dupery", which hurt the trading nation at the expense of specific industries.

In 1799, the Dutch East India Company, formerly the world's largest company, became bankrupt, partly due to the rise of competitive free trade. In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens showed that free trade might benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong in the famous theory of comparative advantage. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics: When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit. The ascendancy of free trade was primarily based on national advantage in the mid 19th century. That is, the calculation made was whether it was in any particular country's self-interest to open its borders to imports. John Stuart Mill proved that a country with monopoly pricing power on the international market could manipulate the terms of trade through maintaining tariffs, and that the response to this might be reciprocity in trade policy. Ricardo and others had suggested this earlier. This was taken as evidence against the universal doctrine of free trade, as it was believed that more of the economic surplus of trade would accrue to a country following reciprocal, rather than completely free, trade policies. This was followed within a few years by the infant industry scenario developed by Mill anticipated New Trade Theory by promoting the theory that government had the "duty" to protect young industries, although only for a time necessary for them to develop full capacity. This became the policy in many countries attempting to industrialise and out-compete English exporters. The Great Depression was a major economic recession that ran from 1929 to the late 1930s. During this period, there was a great drop in trade and other economic indicators. The lack of free trade was considered by many as a principal cause of the depression. Only during the World War II the recession ended in United States. Also during the war, in 1944, 44 countries signed the Bretton Woods Agreement, intended to prevent national trade barriers, to avoid depressions. It set up rules and institutions to regulate the international political economy: the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (later divided into the World Bank and Bank for International Settlements). These organisations became operational in 1946 after enough countries ratified the agreement. In 1947, 23 countries agreed to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade to promote free trade. |

|

Free trade advanced further in the late 20th century and early 2000s:

|

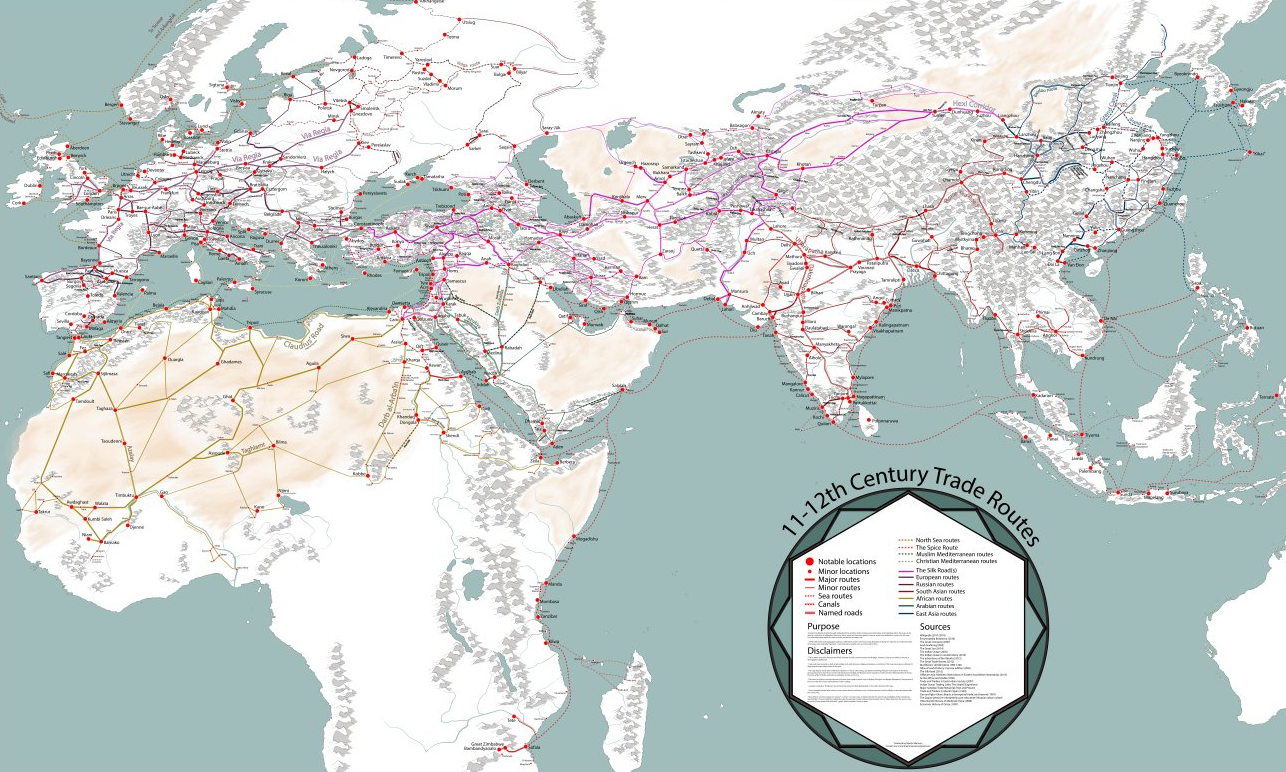

| A FASCINATING MAP of MEDIEVAL TRADE ROUTES |

Globalization is so well established in today’s world that we don’t think twice about where our bananas or socks come from. Long before fleets of container ships criss-crossed the world’s oceans, camel caravans and single-sail cogs transported regional goods across the world. Connecting the World Today’s interactive map, by Martin Jan Månsson, is a comprehensive snapshot of the world’s trade networks through the 11th and 12th centuries, which helped to connect kingdoms and merchants throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe. A confluence of interesting factors helped bring these markets together to encourage commercial activity: |

|

Crusading’s Commercial Corollary

The First Crusade kicked off in 1096, sparking a trend that would have an undeniable economic and cultural impact on Europe and the Middle East. European fighters arriving in the Middle East came into contact with civilizations that were, in many ways, more advanced than their own. Merchants in the area had already been been trading with places further east, and demand for “exotic” goods shot up when crusaders returned to Europe with items both plundered and purchased. The maritime infrastructure used to deliver all those soldiers laid the groundwork for moving goods between ports along the Mediterranean. Some ports, such as Alexandria, had separate ports for Muslim and Christian ships, which helped create a more stable pipeline of trade. The Growing Influence of Cities The dissolution of the Byzantine Empire and the Italian Kingdom left a vacuum that allowed Italian coastal cities to claim prominent roles in regional trade. The port cities of Venice and Genoa were transporting crusading soldiers to the front lines, so becoming hubs of trade in the Mediterranean was a natural evolution. Their geographic locations were also ideal entry points for goods moving along inland European trade routes. In the 10th century, word of Ghana’s abundant gold supply spread to Middle East and actually triggered a rush by Muslim merchants to build connections in the region. A lucrative gold export industry encouraged the growth of cities to the south of the Sahara Desert, which formed critical links between Africa and the Mediterranean trade network. Flying Cash While Italian cities were cementing their role in Western trade, the Song Dynasty introduced an innovation that has important implications today: paper currency. Paper notes, known as flying cash, backed only by the government’s word, helped eliminate the need for heavy coinage and allowed trade to flourish in China. Later on, Marco Polo would famously deliver this idea back to Europe. The Silk Road “The Silk Road” is a catch-all term for the many overland and maritime routes linking East Asia with Europe and the Middle East. Cities and towns along busy Silk Road routes thrived, and during the 12th century, Merv (in present day Turkmenistan) was actually the largest city in the world until it was decimated in 1221 by the Mongol Empire. Trade routes like the Silk Road made the movement of physical goods possible, but perhaps more importantly, they facilitated cross-cultural exchange of ideas, religion, technology, and more. |