|

||

|

| ◄ | INDONESIA |

| __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|

| Indonesia has about 300 ethnic groups, each with cultural identities developed over centuries, and influenced by Indian, Arabic, Chinese, and European sources. Traditional Javanese and Balinese dances, for example, contain aspects of Hindu culture and mythology, as do wayang kulit (shadow puppet) performances. Textiles such as batik, ikat, ulos and songket are created across Indonesia in styles that vary by region. The most dominant influences on Indonesian architecture have traditionally been Indian; however, Chinese, Arab, and European architectural influences have been significant.

The Indonesian archipelago has been an important trade region since at least the 7th century, when traded with China and India. Local rulers gradually absorbed foreign cultural, religious and political models from the early centuries CE. Indonesian history has been influenced by foreign powers drawn to its natural resources. Muslim traders brought the now-dominant Islam, while European powers brought Christianity and fought one another to monopolize trade in the Spice Islands during the Age of Discovery, starting in the early 15th century and continuing to the 17th century. Following three and a half centuries of Dutch colonialism, Indonesia secured its independence after World War II. Indonesia's history has since been turbulent, with challenges posed by natural disasters, corruption, separatism, a democratization process, and periods of rapid economic change. Indonesia is a republic with a presidential system. As a unitary state, power is concentrated in the central government. Following the resignation of President Suharto in 1998, Indonesian political and governmental structures have undergone major reforms. Four amendments to the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia have revamped the executive, judicial, and legislative branches. The president of Indonesia is the head of state and head of government, commander-in-chief of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, and the director of domestic governance, policy-making, and foreign affairs. The president appoints a council of ministers, who are not required to be elected members of the legislature. The 2004 presidential election was the first in which the people directly elected the president and vice president. The president may serve a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms. The highest representative body at national level is the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR). Its main functions are supporting and amending the constitution, inaugurating the president, and formalizing broad outlines of state policy. It has the power to impeach the president. The MPR comprises two houses; the People's Representative Council (DPR), with 560 members, and the Regional Representative Council (DPD), with 132 members. Indonesia has been a member of the United Nations since 1950, and was a founder of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation). Indonesia is signatory to the ASEAN Free Trade Area agreement, the Cairns Group, and the WTO, and has historically been a member of OPEC, although it withdrew in 2008 as it was no longer a net exporter of oil. |

The country has a mixed economy in which both the private sector and government play significant roles and is the largest economy in Southeast Asia and a member of the G-20 major economies. Indonesia's estimated gross domestic product (nominal), as of 2012 was US$928.274 billion with estimated nominal per capita GDP was US$3,797, and per capita GDP PPP was US$4,943 (international dollars).

At World Economic Forum on East Asia in June 2011, Indonesian president said Indonesia will be in the top ten countries with the strongest economy within the next decade. The gross domestic product (GDP) is about $1 trillion and the debt ratio to the GDP is 26%. The industry sector is the economy's largest and accounts for 46.4% of GDP (2010), this is followed by services (37.1%) and agriculture (16.5%). However, since 2010, the service sector has employed more people than other sectors, accounting for 48.9% of the total labor force, this has been followed by agriculture (38.3%) and industry (12.8%). Agriculture, however, had been the country's largest employer for centuries. |

| BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS and BOOSTING ECONOMIES |

|

|

|

|

25 October 2017, Indonesia Netherlands Society held its RT Meeting "The Future of Indonesia: maritime and economic perspectives". Speakers: H.E. Ambassador I Gusti Agung Wesaka Puja, Dr. Rizal Ramli, Prof.dr. D. Henley and others. Case is not to be ruled by foreign powers.

|

|

|

|

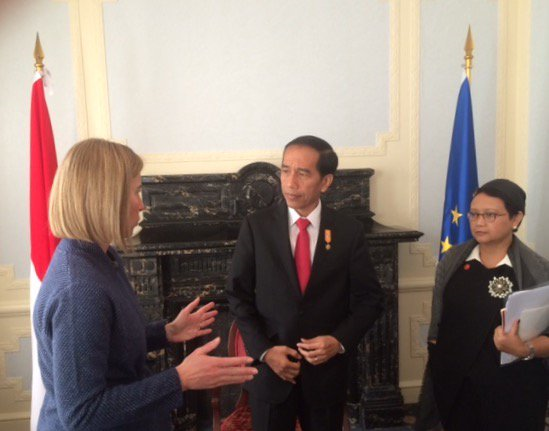

On 22 September 2016, Indonesia Netherlands Society held the RT Meeting "Current State of Play of Indonesia Politics and 2019 Prospects'. Speakers: H.E. Hassan Wirajuda, former Minister for FA and Presidential Advisor of Indonesia, the President of the Dutch Senate, the Ambassador of the Republic of Indonesia, a former Dutch Ambassador to Indonesia, and the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of The Netherlands. Also business was represented.

Importance of the events which took place in Lingaddjati was recalled. After mentioning historical events, attention was given to further development of business, design and functioning of the political system, foreign policy and a more potential to play important role in the world. Credit was alo the transition from dictatorship to democracy. Indonesia is on track. <- photos taken in the library room (Stomps room) of the Senate of the States General of the Netherlands |

| NATURAL DISASTERS (floods) |

|

Severe floods have been reported to have hit Jakarta from 1621 onwards to 2015. An important part of the flooding problem is caused by the fact that a substantial part of Jakarta is low-lying. Around 24,000 ha (about 240 square km) of the main part of Jakarta is estimated to be below sea level. Flooding can become severe if heavy rain happens to coincide with high tides. When this happens, high tides tend to push water into low-lying areas just as the run off from rains in upland areas such as nearby Bogor is flowing down into the Jakarta area. The first pile for a new seawall was sunk October 2014 in Jakarta, Indonesia, marking the start of work on a major coastal protection project on the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) project, which is aimed at countering the effects of soil subsidence and rising sea levels. The project was made possible in part by the efforts of the Dutch government and water sector, who worked with Indonesian partners to develop solutions for the coastal protection of Jakarta. A Dutch consortium prepared the master plan for this unique hydraulic engineering and urban development project. |

| FOREST and PALM OIL |

The PCA (Partnership and Cooperation Agreement) envisages dialogues and working groups on a number of strategic and policy issues including counter-terrorism or peacekeeping operations; economics, trade and investment where the EU has traditionally been the top investor but is losing ground to countries such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore, and people-to-people contacts that include interfaith dialogues and Islamic studies. Furthermore, the signing of the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Voluntary Partnership Agreement (FLEGT-PCA) between both sides last September is expected to boost Indonesian timber and wood exports to the EU. But on the trade front, there exist major challenges which although treated in subdued fashion up to now could eventually embroil Jakarta and Brussels in a troublesome dispute. One such area of tension revolves around the EU policy restrictions and European NGO and consumer campaigns against palm oil, which Indonesia is the world’s largest producer and exporter. Although relatively marginal in European import and consumption terms, it is present as “vegetable oil” in many consumer products and the shipments of palm oil to the EU is significant to Indonesia. And restrictions and publicity against the ecological sustainability of its production have been denounced as “ideological” by Indonesia critics. |

|

|

Typical of the dispute is an article from 2014 in Der Spiegel magazine, “The Dirty business of Palm Oil,” which attacks practices such as brutality against farming populations whose land is turned into palm plantations and deforestation of rain forests. But the PCA itself, which contains clause covering sustainable development, human rights and other major policy issues as well as trade and economic affairs, could provide for closer consultation and cooperation on such potentially difficult issues, as well as such areas as legal affairs, customs, migration, education, culture, energy, transport, tourism, corruption or criminality. In brief, the two leaderships that will guide the EU and Indonesia following this year’s election processes will have a framework for much closer involvement and the opportunity to begin negotiating other specialised accords.

Thus for years the palm oil industry has been under fire. The industry has to contend with accusations linked to deforestation, habitat degradation, climate change, animal cruelty and human rights issues. Policy makers, campaigning organizations and celebrities made bold and extreme statements. The debate is highly polarized and it seems hard to find middle ground. A political response to the connected news was inevitable. The EU plans to ban the use for palm oil for biofuels starting in 2030 (REDII, Renewable Energy Directive). Indonesia is a world leader in the production of palm oil, accountable for approximately 60% of total global palm oil production. In Indonesia, the industry is a major employer providing millions of jobs directly and many more through the activities connected. In the past few years Indonesia and the palm oil industry has been actively working on the above stated issue and is increasingly certifying its activities as "sustainable", "responsible" and "conflict free". This requires collective efforts of producers, traders, buyers, and governments.

Indonesia Netherlands Society organized April 4th, 2019, the seminar "A Broader Perspective on Palm Oil" with the central question "What are best practices in the field and how can Indonesia and the Netherlands work together more closely to overcome challenges in the Palm Oil Industry?" |

| "Indonesia: Lessons for the World" |

THE DIPLOMAT published 21 January 2014 the interesting article "Indonesia: Lessons for the World" by Edward Parker, a writer living and working in Jakarta, who has worked on Indonesian policy issues. He writes here in a personal capacity. All views expressed are his own: While the country faces multiple challenges, it is important to remember how far it has come. The year 2014 will be a pivotal year for Indonesia; one in which the political baton will be handed over. Both the nation’s highest offices will have new occupants: the House of Representatives (DPR) and the presidency. Indonesia will begin a new chapter in its history. The new custodians of Indonesia’s future will face many challenges. Recent months have brought a chorus of criticism as the economy slowed, the rupiah slid, and government policy appeared to lose direction. Commentators have poured scorn on the country’s economic outlook and questioned whether it deserves its status as one of the world’s hottest emerging markets. Everyone knows the challenges; Indonesia needs to push ahead with reforms if it is to move up the economic ladder. Certainly, the country does need to do more to stay competitive, but the tremendous strides it has made should not be forgotten. Just consider where Indonesia was a little more than a decade ago. In fact, looking at Indonesia’s recent domestic accomplishments, what the country has achieved is nothing short of outstanding. After the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime in 1998, many analysts predicted that the country was standing at the end of a precipice, posed to tear itself apart in much the same way as the terrible ethnic conflicts that ravaged the former Yugoslavia. Without a doubt, this was a distinct possibility. With a vast sprawling archipelago of more than 17,000 islands; hundreds of ethnic and linguistic groups, speaking over 300 unique local languages; multiple religious sects; and a huge population, estimated at just over 200 million in 1998, keeping sectarian and ethnic conflict at bay would be a challenge at the best of times. Yet during this tumultuous time, Indonesia was facing political and economic instability, sparking armed separatist rebellions in Aceh and Papua, and secession from Indonesia by the East Timorese in 1999. National disintegration and large-scale ethnic conflict were more likely than not. |

Yet Indonesia managed to navigate its way through this turbulence, emerging as a multi-party democracy with a directly elected president in 2004. The country reformed its institutions, rapidly decentralized its governance structure, and came out the other side with its sovereignty intact. A remarkable feat to say the least. Today, democratic institutions and political stability reassure consumers and attract investors; the streets of Jakarta look a lot more attractive than the streets of Bangkok right now.

Indonesia’s experience offers some lessons for the rest of the world. Indonesia has proven that a vast country comprising a dizzying array of ethnicities, cultures and religious sects can live side-by-side in one nation state. Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, or “Unity in Diversity” is more than just a national motto; it is an underlying principle that has shaped the country. Indonesia has just celebrated Christmas with all of its modern excess and extravagant decor in a Muslim majority country; a celebration of diversity and tolerance, and a true reflection of modern Indonesian values. Don’t let the extremist or the intolerant fool you. These are a mere handful in a vibrant and friendly country of close to 250 million people. Indonesia’s recent experience demonstrates to the newly enfranchised countries of the Arab Spring that democracy and Islam are mutually compatible in a predominantly Muslim country, with a complex dynamic of ethnic groups. This ought to give hope to countries in Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa currently experiencing economic instability, political turmoil and military rule. |

|

Today, Indonesia is one of the most energetic economies in Asia, attracting investors from around the world into a rapidly growing consumer market; this continues despite the slowdown. Growth has slowed but is still strong at around 5.6 percent. Despite the negativity of some commentators, this is still the second-fastest growth rate after China in the G20 group of major economies. |

There has also been much recent controversy over proposed changes to Indonesia’ mining laws; natural resources are undoubtedly important, but Indonesia’s economy is more than just natural resources. Today, the country is characterized by an increasingly dynamic economy and a growing middle class. These middle and affluent classes are likely to double to more than 141 million people over the next seven years, according to the Boston Consulting Group. Young, enterprising, self-reliant and ambitious, Indonesia’s middle class is pushing the economy forward. From banking, to tourism, to entertainment, food and retail, Indonesia’s service sector is driving growth and employment, while contributing to around roughly half of total economic output. Indonesia’ economy has come a long way since 1997 and has undergone a remarkable turnaround.

During the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998, Indonesia was crippled as its banking sector collapsed and the country lost a devastating 50 percent of its GDP; a huge fiscal cost comparable to the recent financial crisis faced by Western economies. However, Jakarta took the hard choices. A decade of laborious restructuring of banks, companies and institutions followed. The banking and financial system was completely overhauled and consolidated from 236 to 128 banks, an independent central bank – the Bank of Indonesia – was created to regulate and supervise the sector and state banks were cut back, with much more room for the private sector. This same banking sector – brought to its knees just 15 years ago – barely coughed during the 2008 financial crash. Indonesia’s institutions acted decisively to stimulate the economy and weather the impact. Indonesia’s experience shows that by being brave enough to make hard choices and undertake necessary radical reforms, economic success can once again be achieved. Many of the continuingly troubled economies of Europe could learn a lesson or two. Indonesia provides an abundance of constructive lessons for the rest of the world. Of course the country still faces many challenges as we head into 2014, but Indonesia has come a long way in a short space of time. It has had transformative successes. The media discourse may focus on the negatives, but don’t forget the huge positives. Indonesia has achieved a lot more than you might think. |

|

| LINGGADJATI |

| Linggadjati

Linggarjati is not only a name given to a little village east of Jakarta in Indonesia, but also the name given to an agreement, which was a political accord. The Linggadjati Agreement, also known as the Cheribon Agreement was a political accord concluded on 15 November 1946 by the Dutch administration and the unilaterally declared Republic of Indonesia. Negotiations took place 11–12 November 1946 in Linggadjati on the slopes of the daunting Mt Ceremay around 25 km towards the south of the West Java city of Cirebon. The Dutch side was represented by Lieutenant General Governor Hubertus van Mook, the Indonesian side by Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir. Negotiations had begun in October 1946 and a ceasefire in Java and Sumatra was agreed to. Recognising their still weakened position following World War II, the Netherlands were more prepared to negotiate with the Republic than they were later in the Indonesian National Revolution.According to the terms of the agreement, the Netherlands agreed to recognize Republican rule over Java, Sumatra and Madura. The Republic would become a constituent state of the United States of Indonesia, which would be established by 1 January 1949 at the latest and form a Netherlands-Indonesian Union together with the Netherlands, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles. The then Dutch Queen would remain official head of this Union. On 25 March 1947 the Dutch House of Representatives ratified a 'stripped down' version of the treaty which was, however, not accepted by the Indonesians. Further disagreements rose over the implementation of the agreement. On 20 July 1947 the Dutch administration cancelled the accord and proceeded to commence military intervention in form of the Operatie Product, the first of two events known as 'police actions'. After the agreements surrounding the Linggadjati Agreement broke down there was a prolonged period of diplomatic dispute and open conflict in Indonesia for much of 1947 between the Dutch and Indonesian authorities. The United Nations Security Council established a Committee of Good Offices which led to the signing of the Renville Agreement in January 1948 on the USS Renville anchored off Jakarta. However the Linggadjati Agreement and the Renville Agreement were at best only partially successful. Disagreements and sharp military clashes between the Dutch and the Indonesia sides continued on throughout 1948 and into 1949. To draw attention and to keep the historical events, occasionally speeches and articles were written. Provided with personal experiences a lecture was held in August 2007 on 'Schermerhorn, Sutan Sjahrir and Linggarjati' in presence of Drs. M. Habib Chirzin president of the Islamic Forum for Peace, Human Rights and Development Millennium, in which values as democracy, freedom, tolerance and the meaning of human rights raised. There are printed drawings made during the negotiations between the Netherlands and Indonesia Linggarjati in 1946, which were added April 7, 2014 to the archive of Prof. Mr. Piet Sanders. The drawings are made by Indonesian artist Henk Ngantung (1921-1991) and were received from Mrs. J. ter Kulve, who in turn received these from Piet Sanders. The pictures give a good impression of the discussions in Linggadjati. The Historical Archives has digitized the drawings. |

|