| In order to prevent total global collapses and disruptions in future, soon necessary

paradigms changes are needed, working on core items as responsibility sharing, innovation, fair trade, tax harmonization, banking activities connected to a banking union and on eco-social thinking and acting.

All of that have to be bound up with our lives inextricably. Ethics, embodyment of a holistic vision, ability to enter into alliances, being smart and to combine are the

heart of the matter.

As example for paradigms changes can serve the report Outlook on the Global Agenda 2012 from the World Economic Forum.

Trichet presented his vision of the Europe of tomorrow ', where he spoke of a 'quantum leap' that should be put. According to him, the internal market should be perfected and structural measures taken and he also insisted on a European Ministry of Finance.

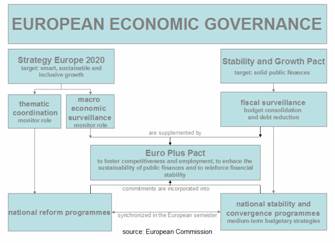

For several years the European Union EcoFin affairs also has been focusing on solving the crisis, but now the European economy has to get back on track. The European leaders discussed this around the European Semester 2012, the monitoring of the economic policies of the member states. Due the Summit, Jacques Pelkmans and MEP Corrien Wortmann lectured 27-02-2012 on search for economic growth in Europe. The state of the global economy is in poor condition. The existing global financial architecture (Clingendael Policy Brief September 2012) is structurally flawed and puts in motion a rising demand for effective economic and financial policy governance on a global scale.

|

|

This development represents challenges for European countries (e.g. the Netherlands and Belgium). These countries want problems recognized and solved, and they can hardly accept to play often no role of significance in (some) coalitions anymore

Multilateralism-light, as defined under the G20, will - in theory - give green light, but only if allowed.Several countries were not allowed to participate the recent G20 summit in Mexico (18-19 June 2012) anymore. From 1 November 2012 trustee positions in the IMF of Belgium and the Netherlands are combined (*). It also seems inevitable that in time also at the World Bank emerging countries will get priority to represent their interests.

(*) There is a report of the Dutch delegation to the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944, which summarizes about some delegations, including Belgium: "The relationship between the Dutch and Belgian delegates can only be called excellent. There was constantly a very close contact between the two delegations, which showed that their insights on every point were entirely similar. The close cooperation has undoubtedly strengthened and greatly amplified the position of Belgium and the Netherlands at the conference. By acting jointly, the delegations represented an extremely important element in the international monetary and trading system and as such they were thus recognized. The good cooperation led, among other things, to a quota system where the Netherlands and Belgium were represented both in the Bank and the Fund as executive director or alternate executive director. This opens the possibility to get an appointment with the Netherlands, for example, during the first two years a Director designated for the Fund and an alternate for the Bank and Belgium a director for the Bank and an alternate for the Fund, while for the next period 2 year roles would swapped, etc. By the close contact and exchange of information and insights both delegations retained a complete overview of the work of the conference, since either Netherlands or Belgium was represented in almost every subcommittee or special committee". |