| Speech by High Representative Federica Mogherini at the UN Security Council on the European Union – United Nations cooperation 6 June 2016:

Monsieur le Président, Monsieur le Secrétaire General,

Ambassadeurs, chers amis,

Je souhaite tout d'abord remercier la Présidence Française pour l'organisation de ce débat – pour la deuxième fois en un an- , et pour sa capacité à construire des convergence globales. Celle-ci nous a permis d’obtenir le succès que l'on a vu sur le climat à Paris. Je veux aussi envoyer mes meilleurs voeux à nos collègues et amis musulmans pour le début du Ramadan.

I shall switch to English. When we last discussed cooperation between our European Union and the UN one year ago, I had just taken office as the Union’s High Representative, and it was my first time in the Security Council. Since then, I came back to this room also to discuss migration and our fight against terrorism. And I cannot count all the exchanges, the meetings, the common work I’ve done with UN agencies all around the world, and with so many of you, in different multilateral formats.

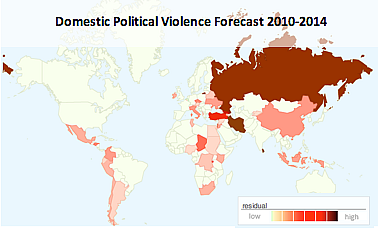

I believe this is the only way we have – as Europeans, as responsible members of the international community – to face these difficult times in the history of the world. The entire Middle East is in turmoil – with so many forces trying to redefine the regional balance of power, and so many people calling for an end to their suffering.

Inequalities are on the rise in big parts of the globe. Climate change is challenging the economy and the security of large parts of our world. An unprecedented number of people is on the move. Tens of millions are fleeing from war, looking for a chance of survival, or for a better life.

We often say that Europe is facing a refugee crisis. Let us always remember: this is first and foremost a “crisis” for the men, women and children who are going through it, as they flee their homes. And it concerns the whole world, it’s a global issue, not just a European one.

But indeed our own continent faces a great deal of challenges.

Our cities have been hit by terrorist attacks – just like so many other places in the world, in Africa, Asia, America. Hatred and violence are growing within our own societies. Together with inequality and insecurity, xenophobia, Islamophobia and anti-Semitism are also on the rise. In times like these, we need each other. We need all nations to come together, united. We need the United Nations. Because only together we draw the way forward, and make sure that tomorrow will be better than today.

One year ago I told this Security Council that our European Union believes in multilateralism and believes in the United Nations. Today I can add that multilateralism will be one of the core principles and priorities in our new Global Strategy for foreign and security policy, which I will present in the coming weeks. But what truly matters to me, is that we are turning this commitment to multilateralism into practice, on a daily basis. This has also been possible thanks to you, Mr. Secretary General, and to the whole senior leadership of the United Nations. Our cooperation in these months and years has been truly excellent. And this makes such a difference, in so many places in the world.

Our European Union has put multilateralism at the core of our common external agenda. We have learnt the hard way, that unilateralism doesn’t pay off. This is no time for global policemen. This is no time for lonely warriors. If we want to finally put an end to the many crises we face – and most of all if we want to prevent new ones before they explode – our only hope is to work as truly United Nations. The hardest the task, the stronger our cooperation must be.

MIDDLE EAST PEACE PROCESS

In a moment I will talk about Syria, Libya and other crises that are constantly on top of our common agenda, and also of the news cycle. But let me start with a much older conflict, that will soon enter its eighth decade. Let us not wait for the next open war between the Israelis and the Palestinians. Because this is what will happen, if they don’t go back now to meaningful negotiations.

The proliferation of conflicts and crises in the region of the Middle East is not a reason to forget about the fate of the Israelis and the Palestinians. On the contrary. The new security threats in the Middle East should push everyone to renew our efforts towards ending this conflict. This is first and foremost in the interest of every singe Israeli and every single Palestinian – and the events in the rest of the region make it even more urgent than in the past.

A further escalation, especially around the holy sites in Jerusalem, would have grave consequences for the whole region. On the contrary, peaceful solution to the conflict – with bold leadership by both sides – could unlock genuine regional cooperation. The Israelis would benefit from it, and the Palestinians would benefit from it.

The entire Middle East, Europe and the world – we would all benefit from peace. It would set a new paradigm of cooperation in the Middle East. Peace in the Holy Places would send such a powerful message to the entire world.

That is why I made the Middle East peace process – if it can still be called a peace process – a top priority for our action, in the very moment when the perspective of the two States is getting beyond reach. |

|

|

The possibility of a secure State of Israel and a viable State of Palestine living side by side is fading away. And together with the perspective of the two-States, peace would also get beyond reach. The trends could not be more clear. First. Violence and incitement are not just inflicting terrible human suffering: they amplify the mistrust between the two communities. Second. Israel’s policy of settlements systematically erodes the prospects for a viable two state solution. It also raises serious and legitimate questions about the real Israeli leadership’s ultimate goals. Third. The lack of unity between the Palestinian factions is still a major stumbling block. Each of these trends – alone and combined – could make the two-State solution impossible to achieve. We would risk the collapse of all hope.

The Israeli and the Palestinian leaders hold a responsibility towards their people, towards the region and towards the world. They can halt destructive policies and rhetoric, reverse the trend, and finally rebuild the conditions for meaningful negotiations. The future of it is in the hands of the two peoples, and of their leaders. Right now, we all know there is no peace process at all. And the international community can’t just sit and wait till the next war.

We keep believing in Europe that the entire world has to do its part. Last year, the European Union pushed to revitalise the Middle East Quartet. We have had several meeting at principals’ level, to draw together the way forward. Here in New York we invited Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and the Arab League to also join the discussion. The cooperation among our envoys has proceeded for months. So let me thank the United Nations, the United States and Russia for all the common work we have done so far. A few days ago in Paris we discussed how the international community can help and accompany this work.

As you know the Quartet Report will be made public very soon. We will describe very frankly the immediate obstacles to direct talks, and the policies that threaten the viability of a two-State solution. We will also make clear recommendations on the way forward. With one main goal: to recreate some confidence between the two sides, and the conditions to go back to meaningful negotiations. Because we are convinced that the current stalemate is not sustainable: there is no status quo, and we all know it. If the situation does not improve, it will get worse. And this is something no one can afford – no one, and first of all the Israelis and the Palestinians.

SYRIA

We need to be as realist as we can in analysing the difficulties, risks and threats of the region and of today’s world. But we also have to recognise the signs of hope when we see them, or when we manage to build them. It is a strong reminder that change is possible, and change for the better, if the international community is united and focused.

Just in July last year this Council endorsed our deal on Iran’s nuclear program. The deal in itself was a major success of patient multilateral diplomacy. Six months later the deal was implemented. And we keep monitoring the full implementation of all its parts, counting also on the good cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency. In parallel, the European Union is working to make sure that the benefits of the deal reach the Iranian people and improve regional cooperation.

Because after the deal we all knew we had to build on the positive momentum. In November we met again in Vienna, where the deal was signed, with a new International Syria Support Group. For the first time since the beginning of the war, all regional and international actors were finally at the same table. Since then, let me say that Staffan de Mistura has been doing a truly amazing job, and much has been achieved. But we all know that the process has come to a critical point. It is vital that humanitarian aid reaches a greater number of areas. It is vital for too many people in need for help, and it is vital also for starting real negotiations among the Syrian parties in Geneva. We know how fragile this whole process is – and probably it will continue to be. So much blood has been shed, and national reconciliation won’t be easy at all. But there is no other way to stop the carnage, give hope to the Syrians and defeat Daesh.

Europe is doing its part: we reopened our humanitarian office in Damascus, we are engaged on the ground as the first donor to Syria and the Syrian people, and we play our role in encouraging and accompanying the political track. Staffan de Mistura knows he can always count on our full and active support.

I was myself personally in Geneva, meeting the parties upon his request, during the last round of talks. All international actors need to do whatever they can to make the cessation of hostilities work, the delivery of humanitarian aid move and the negotiations start, and finally move towards a political transition for Syria. Our divisions – here in this room, in the international community, in the region – would only benefit Daesh, and chaos.

IRAQ

And as I mentioned Daesh, Iraq must also remain high on our agenda – as a centrepiece for stabilisation in the broader region. Good progress has been made in the military campaign. The fight in Fallujah is on-going as we speak. But there are also concerns: the liberation of areas must be followed by rapid stabilisation and restoration of services. The EU is doing its part and will continue to contribute to both humanitarian and stabilisation needs.

And the campaign against Daesh needs to be framed by an adequate political settlement. We continue to support Prime Minister Abadi’s efforts in this respect. All political players must seek a swift resolution to the current political impasse. We remain as international community committed to the unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Iraq. |

|

|

LIBYA

And unity of the international community and of the region is also central for Libya. I know some had lost hope that the Presidency Council would ever be formed and arrive in Tripoli. But they have, and this would not have been possible without this Council’s unity and Martin Kobler’s excellent work. I know he is briefing you in a few hours, so I will limit my remarks to the European Union’s work on Libya – in strong coordination with him. In Vienna, last month we all restated our support to the government of national accord. Our European Union has started to mobilise a package of 100 million euros to make Libya’s new start possible and make Libyans live their lives in safety and dignity. Which is what they deserve.

Last month the Libyan government has invited our Union to provide training to the Libyan coast guard and navy. I spoke with Prime Minister al Serraj about the modalities last Friday. For us it is key that anything we do is planned and delivered according to Libya’s full ownership and Libya’s priorities. Training the Libyan coast guard and navy will be an opportunity to put Libyans in the conditions of saving lives at sea, dismantling the criminal economy of human smugglers, controlling the countries territorial waters effectively, and creating a safe environment for Libyan fishermen.

Let me spend a few more words on how we are working in the Mediterranean. Last spring, when we decided to launch a naval operation – Operation Sophia – against the traffickers’ networks, we asked for a Security Council resolution to endorse our mission. You were impressively united in doing so, and I thank you for that. Since then, thousands of lives have been saved, over a hundred assets seized and many traffickers brought to justice. On 23 May, we decided to extend that mandate of the Operation by a year.

Now, once again, we are asking this Council to adopt a Resolution on authorising Operation Sophia to enforce the UN arms embargo on the high seas, off the coast of Libya. This is the course of action that our European Union has chosen: constant coordination with the United Nations, to best serve our collective interests, the interest of the international community as a whole. This is the place where international action should be discussed, decided and authorised. And I can only hope that this Council will once again do the right thing, and help us make the Mediterranean a safer place, for everyone starting with our Libyan friends.

YEMEN

With so many crisis taking the headlines, Yemen risks not to get the attention it deserves. Yet, the need for a political solution and for addressing the dire humanitarian situation is just as urgent there as it is elsewhere in the region and in the world. We support the Special Envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed in his work. Progress has been made during the peace talks in Kuwait in the last five weeks, and I thank Kuwait for that. We should encourage the parties and players in the region to seriously engage with a constructive attitude.

UKRAINE

While we deal with Syria, Libya, Yemen, we could not forget of other crises, including at our Union’s Eastern borders. The end of the conflict in Ukraine remains a top priority for the EU. The Minsk agreements have to be fully implemented in all their parts, if we want the situation in eastern Ukraine to calm down. The UN office for coordination on humanitarian affairs is doing a precious job in mapping and organising humanitarian assistance there. The UN reports on human rights in Ukraine – financed by our European Union – are also of great help to monitor the situation.

The European Union will continue to stand for Ukraine’s territorial integrity – and does not recognise the illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. We are working closely with Kiev to help them achieve the reforms the country so urgently needs. So let me mention the important constitutional amendments approved just days ago, which will improve the efficiency and independence of the judiciary. But they really matter because they can also build momentum for the adoption of the amendments on decentralisation and other reforms. It is an important achievement. It is also an important opportunity to move the country forward – and to address the needs of all the citizens of Ukraine.

GLOBAL SECURITY PROVIDER

But our cooperation with the United Nations goes well beyond our immediate region. The more I travel the world, the more I realise that many of our partners already consider our Union as a global security provider.

Colombia might sound like a far away place to many Europeans. And yet, we are following very closely the negotiations that could put an end to one of the world’s older conflicts. I was there just a few days ago to sign some important agreements, bringing already our concrete support to the peace process and in particular to the demining efforts. I confirmed to President Santos our willingness to engage even more on the implementation of the deal, as soon as it will be reached. Our coordination with the planned UN observer mission will be crucial.

Moving to the other side of the world, next October we will host in Brussels a major international conference on Afghanistan. After so many years, a peaceful Afghanistan will only be possible if regional powers and the international community will also unite and accompany the peace and reconciliation process, and the economic and social development of the country.

On this and on many other files the unity of the Security Council is one of the most powerful assets in our hands, for promoting peace. For instance, a greater involvement of the Council to monitor the security situation in Burundi would be most welcome. A UN police mission could deter further threats to peace in the country, and the EU stands ready to cooperate with the United Nations to this end. |

|

|

Our common work can build on so much positive experience. Take the Central African Republic, where the EU and the UN joined forces to restore the basic functioning of the police and gendarmerie. Our efforts contributed to the political transition and the instalment of new, democratically elected authorities.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, our European Union keeps supporting the work of MONUSCO and of UN agencies. The current political uncertainty risks to evolve into a full blown crisis, with spill-overs in an already fragile region.

In fact, our common work cannot be limited to crisis management. Even if these difficult times require much of it. Still, the best way to address a crisis is to prevent it. And this is a field where the UN and our European Union can do so much together.

RESILIENCE

When we discussed Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals, it was clear to everyone that Europe and the UN shared the very same approach to security and development. When we invest in growth, we are also investing in security. Our cooperation has started to yield results. The Paris agreement on climate, the Sustainable Development Goals – these are opportunities to overturn a narrow and short-term concept of security. We will now work to ensure their full implementation.

MIGRATION

The same approach has now become integral part of our response to migration and the current refugee crisis. I have already mentioned our Operation Sophia, and the great job it is doing together with Frontex, the Italian vessels and our partners – including NATO – to save lives and chase human smugglers. But there is much more than that. We need to prevent that those lives are put in danger – both at sea and in the desert, where thousands die far from our eyes and our TVs.

This is why tomorrow I will be in Strasbourg to present, together with my colleagues in the European Commission, the plan for a new “migration partnership” with our friends in our region and in Africa. Migration and displacement are one of the great challenges of our era. Our response is the measure of our very humanity.

There are some key facts that Europe cannot overlook, which will be central to our new partnerships. We too often forget that countries like Ethiopia or Kenya, let alone Lebanon and Jordan, host huge numbers of refugees. Hospitality is not an easy task: we experience it every single day. The closure of the Dadaab camp in Kenya could have dramatic humanitarian consequences – and our European Union is following the issue very closely, together with the United Nations and all relevant agencies.

For these reasons we will further reinforce our Trust Funds, which are already providing healthcare and food to those in need, and are creating jobs for the refugees and for their host communities. But we also know that public money alone will never be enough. So a key component of our migration partnerships will be to attract private investments on key projects. Africa has a huge potential for growth, and we must manage to get the private sector on board.

We must also offer opportunities: the best way to dismantle the illegal business is to work on legal avenues for human mobility. Europe needs to do its share, but we also count on our partners here – in the UN and in this Security Council – to do the same. I do look forward to the Summit in September, where migration will be recognised for what it is: a global phenomenon, concerning all of us.

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

Stronger partnerships are the building blocs of our foreign policy. All today’s challenges transcend borders and national sovereignties. None of us, alone, can carry the weight of the world on its shoulders. But we all have a role to play, together with others, in a multilateral framework. So our European Union will seek more and more to reinforce old ties and create new ones. This is true in our bilateral relations, but it is even more true on a regional and global level. A network of regional alliances can truly contribute to global peace and security.

That’s why we invest in regional networks and organisations. For instance, we have supported African-led peace efforts through the Africa Peace Facility since the very beginning, with more than 1.6 billion euros in the last ten years. It is now time to make sure that Africa’s capacities are provided in a more sustainable and efficient manner. This is first of all in Africa’s interest, to strengthen the continent and its regional structures against the many challenges it faces.

Our cooperation with the African Union, with the Arab League, with CELAC and ASEAN can only grow stronger. In some parts of the world, we need to strengthen existing organisations. In other cases, we need new and creative formats. Our recent experience with Libya and Syria shows the effectiveness of ad-hoc formats working in close coordination with the UN envoys.

Despite all setbacks, despite all the stops and goes, multilateralism has shown its strength. Formats can change, and institutions must be reformed. But in our conflictual world, where power is scattered and diffuse, global peace and security only stands a chance if our nations and our regions are united. Our European Union will always come back to the United Nations, to the core of the international multilateral system, to the stubborn idea of a cooperative world order.

Thank you.

New York, 6 June 2016 |

|